“How low can you go?” ~Chubby Checker, The Limbo Rock

By Catherine Austin Fitts

The slow burn’s squeeze on household budgets is weighing heavily on both individuals and institutions. Let’s take a look at what low interests rates mean to savers.

In 1990, a $100,000 bank deposit would have earned savers approximately $8-9,000 in interest. Today, the return is next to nothing. And interest rates, after starting to turn up last year, have moved back down instead. Since 2009, savers have received a return on their $100,000 asset of approximately $2,000 instead of $40,000.

[Click on chart for larger image]

The beneficiary of low interest rates has been the US government, as well as other global governments. Large corporations have also accessed long-term capital at very low rates through the bond markets. The drop in rates has lowered mortgage rates but has not translated through to lower rates on student loans or credit card debt.

Since 2008, a US citizen with a median household income probably paid approximately $25-35,000 in federal taxes. That bites hard when the infrastructure you are funding is 1) deliberately managing its finances outside the laws related to financial management of government accounts and 2) consistently implementing policies that are harmful to household finances. Example: the pump and dump of the housing market with the resulting fraudulent securities bailed out with taxpayer’ credit.

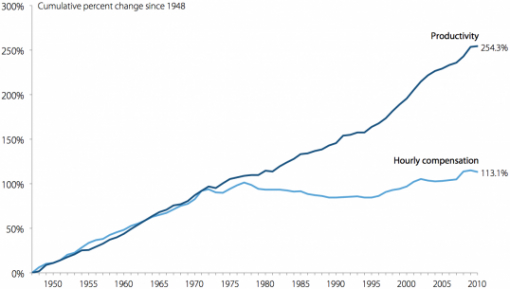

Federally implemented monetary and fiscal policies have ensured that productivity gains go to shareholders and to private investors — not to labor. So an important aspect of the slow burn is that wages have been stagnant. Of course, those who listened to Sir. James Goldsmith in 1994 knew that this would happen. In essence, inflationary monetary policies have been (in part) intentionally offset by labor deflation engineered through globalization.

So, when personal finance magazines tell you to make up for lost savings from lower interest rates by working harder or longer and saving more, well that’s quite a double-bind.

[Click on chart for larger image]

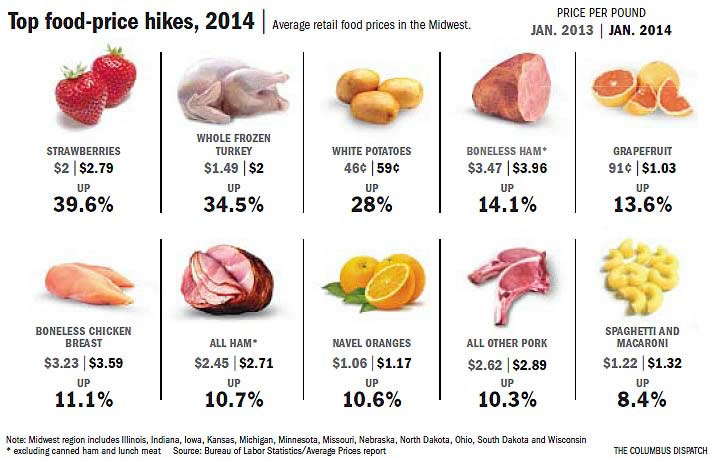

Make that double-bind, in fact, a triple-bind: the price of essential items such as food have been going up.

[Click on chart for larger image]

The accumulated impact of low interest rates is a growing concern for insurance companies and pension funds. Low returns will have a serious long-term impact on such institutions’ ability to deliver on annuity and insurance products and pension benefits. That can translate to more bad news for household finances.

It is not surprising that we are starting to see serious studies from the institutional sector on this issue – one last week from insurance giant Swiss Re and one recently from McKinsey Global Institute. Lower returns and growing concerns about liquidity in the fixed income markets appears to be contributing to the the shift into equities – seeking dividends from companies that can endure whatever happens in the debt market and a global debt restructuring.

Global debt is growing. And the more it grows, the more we build an infrastructure that depends on low interest rates and standing in line for central bank and government largesse.

What can you do? Well, you can invest your time and resources in understanding and outwitting the slow burn rather than spending your time in ways that drain you even more.

For example, instead of using several hundred hours to pay attention to the US presidential election, let alone to donate money, take the time and money and start your own orchard and edible landscape. Or implement changes in your home that reduce energy expenses.

Or, learn new skills that increase your income or lower your taxes.

Example: I just read a story by a woman who moved to Istanbul to teach. She rented an apartment for $750. With her landlord’s permission, she started renting a room in her apartment on Airbandb. She says she is making $2,000-4,000 a month renting the room. She says she is living well and is now adding to her savings monthly.

See the game – then act!

Related Reading:

Swiss Re: Financial Repression — The Unintended Consequences

McKinsey Global Institute: QE and Ultra-Low Interest Rates; Distributional Effects and Risks