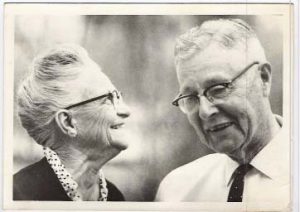

Franklin’s Grandparents, Mr. & Mrs. Harvey Baldridge

By Franklin Sanders

As I was writing this newsletter, on Monday, my brother called to tell me that my mother had passed away. She was 95, and had been in a nursing home for five or six years. She couldn’t hear anything, and didn’t recognize anyone, so her death has to be viewed as a merciful release from a puzzling time.

My mother was born in 1915, out in the country in central Arkansas, at a place called Quitman, on 19 June. My grandmother had already lost two babies to miscarriage, so when tiny twins were born about the size of a bullfrog, she didn’t have much hope they would survive. On advice of my greatgrandfather, I believe, they made a fire in the cook stove and put the twins in there to keep them warm. My brother the doctor believes that my mother was hard of hearing all her life because they put her on the fire box side of the oven. That would have been much warmer, and might have prevented the small bones in her ear from forming properly.

Obviously, the twins, my mother Ara Ruby and her sister Ava Ruth, survived. My grandfather, Harvey Baldridge, who never liked farming, moved his family to Conway where he worked at everything, eventually managing the cafeteria and maintenance at the teacher’s college there. My mother and her sister both became teachers. Mother was teaching in eastern Arkansas at a place called Earle when she met my father, who was teaching and coaching.

There are so many people in the world, and when we pass time closes over us like the waves of the sea. Oblivion swallows us up. Sure, our passing means something to our children and grandchildren, and, if we have a very tight and self-aware family, perhaps to great-grandchildren, but at last time’s waves close over us and we are forgotten even to our own blood.

Or are we? After I was converted as a grown man I came across the will of my great-greatgreat-great-great-great-great grandfather, William (I believe) Baldridge. Written about 1725 it began something like this, “I, William Baldridge, being of sound mind and weak body, but nothing doubting that I shall receive it back at the general Resurrection, do make this last will and testament.”

Our time and our vision are so short we can only barely discern God at work, yet here before my stunned eyes were words from beyond the grave to limn for me the careful planning and divine labor in my own creation and descent and calling. God works, after all, in covenants, through families, over time.

Zacharias sings that God made the promise “to Abraham, and to his seed forever.” The mere fact that we keep on having children holds always before our dim eyes the faithfulness of God, but especially his faithfulness in blessing our work, of assuring us that it is “not in vain.” Do the waves of time close over us without a trace left behind? Not at all. Because God meant us to be, everything we do has meaning, and none of it is in vain, nothing and no one forgotten.

So looking back on my mother’s life, in spite of all the sins and shortcomings inevitable in any human being, I can still hear the words of welcome that greeted her:

“Well done, thou good and faithful servant.

Enter into the joy of thy Lord.”

And that joy time cannot swallow up.

God bless you all,

Franklin

Note from Catherine:

For readers who have enjoyed Franklin and his many good works and wish to express their appreciation at this time, I am sure the Sanders family would welcome contributions in Ara Ruby Sanders’ name to the Christ Our Hope Reformed Episcopal Church:

Christ Our Hope RE Mission

PO Box 178

Westpoint, TN 38486